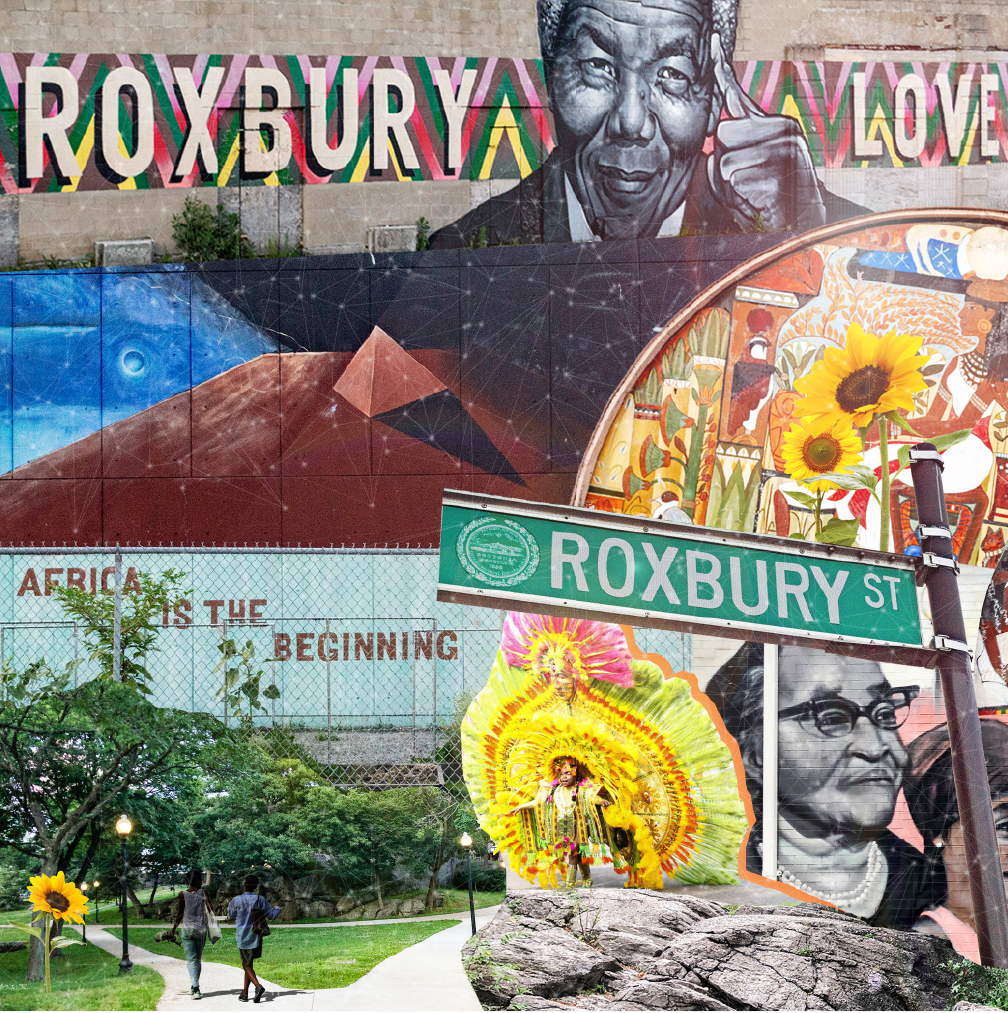

Roxbury is a gem of Black arts and culture in the heart of Boston.

— Kelley Chunn

Throughout history, Roxbury has always sat at the crossroads of culture and exchange in the greater Boston region. During early history, the neighborhood has been home to waves of immigrants—including Irish, Jewish, Scandinavian, Italian and Latvian populations. Starting in the 1940s, Roxbury has grown into a hub of Black arts and culture in the heart of the city. Particularly in the 1960’s and 70’s the neighborhood was almost entirely Black, and sat at the center of activism and community organizing efforts to fight for justice and civil rights within the city of Boston and our greater society.

Over the years, Roxbury has served as a testament to the diversity of people and cultures across the Black diaspora—including African-American, Indigenous, Caribbean, and African immigrant communities.

Today, Roxbury remains a majority Black neighborhood, yet not as racially concentrated as it has been in prior decades. Still, the culture and history of the neighborhood remains strong.

Population

8% of Citywide population

Black/African-American population

Second highest neighborhood concentration of Black residents citywide

*Via Boston in Context 2019 Report,

2013-17 ACS Data

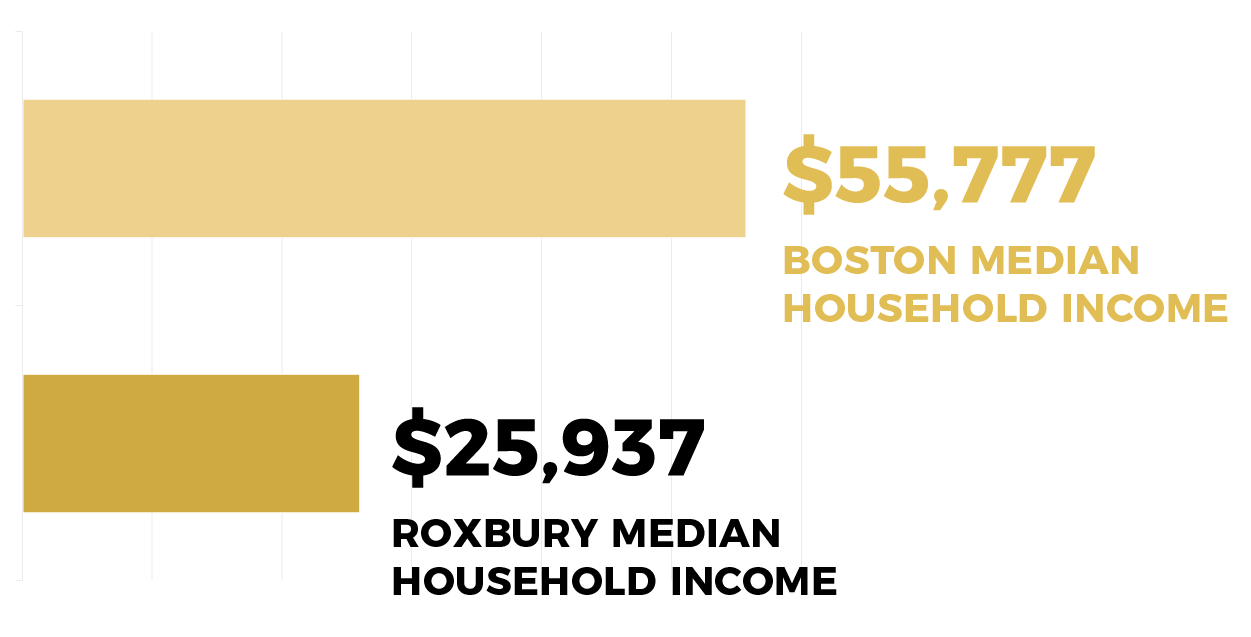

Roxbury is a community with great pride, history, community, and resilience—but challenges around wealth and resources, and poverty concentration, and racially-motivated disinvestment. In the 1960s-70s, a significant portion of lower Roxbury was demolished to make way for the proposed Southwest Expressway highway. Residents across neighborhoods were successful in halting the highway’s construction, yet significant demolition and displacement had already taken place. During this time, the elevated rail that once passed through Dudley Square (now Nubian Square) at the heart of the district was taken down and moved to the edge of the neighborhood. Today, the city still holds onto many demolished parcels that have remained vacant for decades.

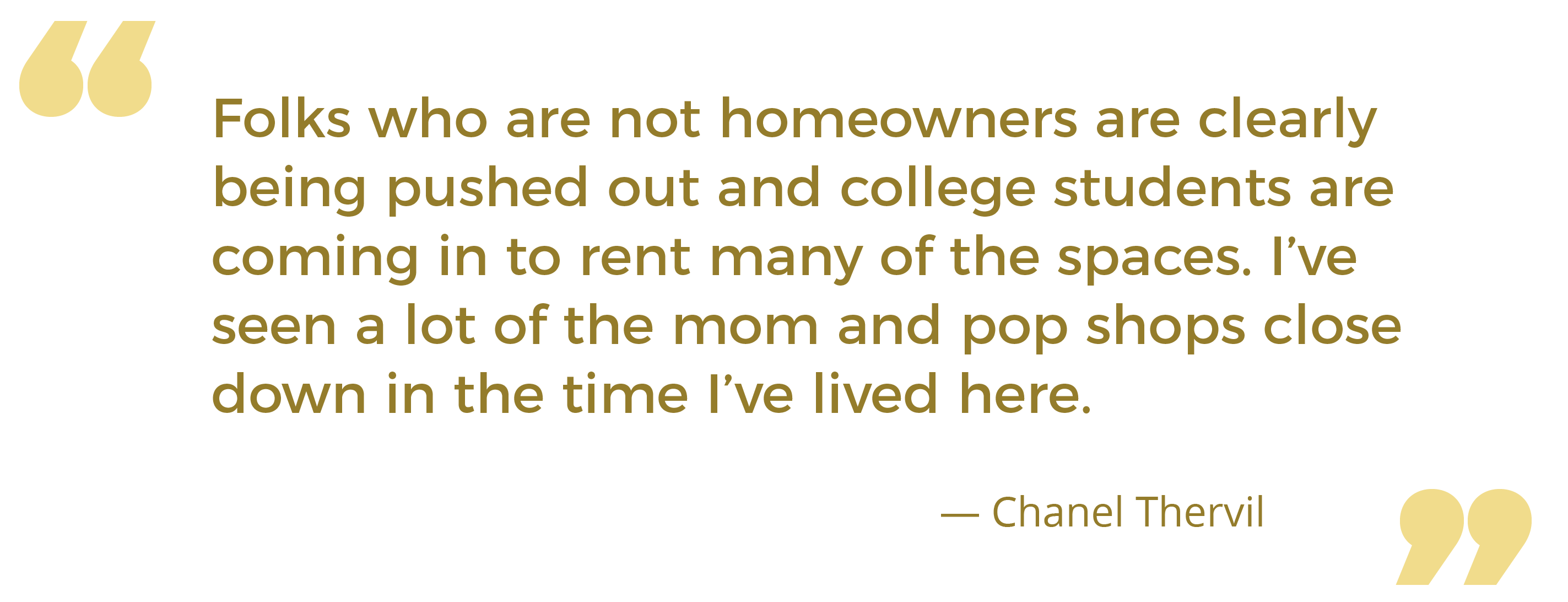

Gentrification and property affordability are identified as key issues facing Roxbury today.

Rising property and rental costs are displacing many former residents, primarily marked by trends of low-income Black residents moving further to the margins of the city, and college students and white millennials moving into the neighborhood. Median home values have nearly doubled in the past five years, from a median sale value of $230,000 in 2013 to $430,000 in 2018 (via Zillow).

To date of this research (2019), city-driven planning processes in Roxbury have continuously failed to address the core needs of the developing strategies to empower residents to build stable wealth and ownership through both home and business ventures.

Overwhelmingly, respondents described Roxbury’s greatest strength as its people, history, and lasting legacy of activism and cultural expression from the past into the present.

In Roxbury, historical narratives through lived experience hold strong. The power of Roxbury’s culture has been cultivated through generational connections and knowledge sharing. Spaces for communal gathering—whether for family, religion, artistic expression, political action, or otherwise—have helped to ensure that Roxbury’s history is one that is carried forward into the present.

Like many Black communities across the country, Roxbury holds many landmarks that are still named from the colonial era. Despite this context, the valued spaces within the neighborhood highlight how the community has claimed and co-opted space over time in an environment that was never designed or built for them. Whether through physical or social intervention, formal or informal means, the narratives of Roxbury’s residents have reflected themselves in the landscape.

Throughout the years, Roxbury has been the grounds to a breadth of leaders for civil rights and the betterment of the livelihoods of Black people. These leaders include household names like Martin Luther and Coretta Scott King, Malcolm X and Melnea Cass, residents who carry generational lineage in the neighborhood, and newcomers who have found home belonging within the community where they have not elsewhere in the region.

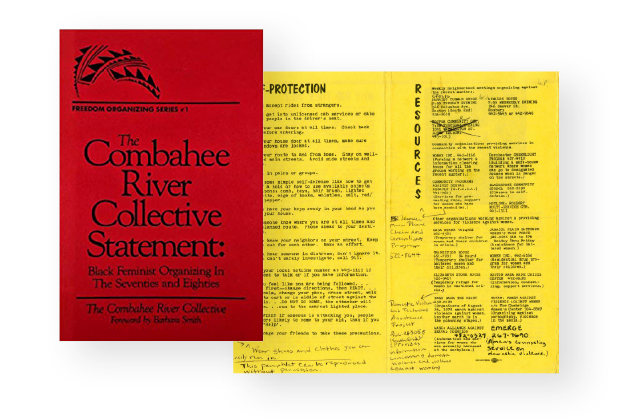

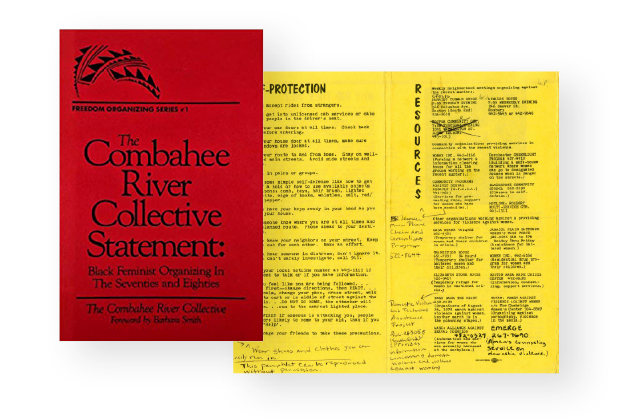

Here, we recognize that past and present collaborative efforts amongst Black womxn to claim space, honor history, and build pathways for health and healing for future generations. Core to these efforts is the underlying message that space for Black womxn is not always going to be given, often it must be taken and reclaimed through guerrilla tactics to fully acknowledge their needs.

The Peoples’ Free Health Center clinic was organized by collective volunteers, providing free medical services to the community—most notably sickle cell anemia testing. The clinic also held classes to educate and empower community members to learn first aid and train as lab technicians. Operated by the Black Panther party, the clinic occupied a site illegally at the intersection of Ruggles and Tremont Street on land that had been seized from the community by the Boston Redevelopment Authority. Beyond providing free health services, the clinic’s location stood reclaim land and block to the proposed highway route slated to cut through the community.

The Combahee River Collective was a Black queer feminist group active in Roxbury and Greater Boston. Through the development of a Collective Statement, their writings laid the groundwork for ongoing radical Black feminist movements and language on intersectionality as a framework for liberation. Beyond writings, the collective was active in political struggles around police brutality and the public school desegregation busing crisis. In 1979, the group developed a series of informational pamphlets for the community to build awareness and safety precautions in response to a series of murders against Black womxn that took place that year.

Carrying on the legacy of the Combahee River Collective, the Estuary Projects is a guerrilla installation series to memorialize the lives of 11 Black womxn who were murdered four decades prior. At the time of their deaths, their stories were largely ignored by dominant media outlets. Led by Kendra Hicks and a collective of volunteers, temporary memorials were created at each site on the 40th anniversary of each woman’s passing, remaining up for 24 hours. At each location, the community held space through ritual and gathering to memorialize each woman’s life—making peace with history and sending lingering spirits into safe passage.

We asked respondents...

View all mentioned spaces on the interactive map below. Response are inclusive of both survey and interview feedback.